Confidence and affection from my peers

GEORGE WASHINGTON - JOHN ADAMS - JAMES MADISON - JAMES MONROE - JOHN QUINCY ADAMS - ANDREW JACKSON - MARTIN VAN BUREN - WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON - JOHN TYLER - JAMES K. POLK - ZACHARY TAYLOR - MILLARD FILLMORE - FRANKLIN PIERCE - JAMES BUCHANAN - ABRAHAM LINCOLN - ANDREW JOHNSON - ULYSSES S. GRANT - RUTHERFORD B. HAYES - JAMES A. GARFIELD - CHESTER A. ARTHUR - GROVER CLEVELAND - BENJAMIN HARRISON - WILLIAM MCKINLEY - THEODORE ROOSEVELT - WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT - WOODROW WILSON - WARREN G. HARDING - CALVIN COOLIDGE - HERBERT HOOVER - FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT - HARRY S. TRUMAN - DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER - JOHN F. KENNEDY - LYNDON B. JOHNSON - RICHARD M. NIXON - GERALD R. FORD - JIMMY CARTER - RONALD REAGAN - GEORGE BUSH - WILLIAM J. CLINTON - GEORGE W. BUSH - BARACK OBAMA - JOSEPH R. BIDEN - DONALD J. TRUMP

President George Washington

Mount Vernon 10th May 1786

The favourable terms in which you [Lafayette] speak of Mr Jefferson gives me great pleasure: he is a man of whom I early imbibed the highest opinion—I am as much pleased therefore to meet confirmations of my discernment in these matters, as I am mortified when I find myself mistaken.

New York Jan 21st 1790

I consider the successful Administration of the general Government as an object of almost infinite consequence to the present and future happiness of the Citizens of the United States. I consider the Office of Secretary for the Department of State as very important on many accts: and I know of no person, who, in my judgment, could better execute the Duties of it than yourself.

Mount Vernon, April 3d. 1791

Until we can restrain the turbulence and disorderly conduct of our borderers it will be in vain I fear to expect peace with the Indians — or that they will govern their own people better than we do ours.

Mr. Jefferson's idea with respect to the dispatches for me, is a very good one, and I desire it may be put into Execution.

Mount Vernon 4th. Octr. 1795

Your letter of the 12th. Ulto., after travelling to Philadelphia and back again, was received by me, at this place, the 1st. instant.

The letter from Madame de Chastellux to me, is short—referring to the one she has written to you for particulars respecting herself and infant son. Her application to me is unquestionably misplaced, and to Congress it would certainly be unavailing, as the Chevalier Chastellux’ pretensions (on which hers must be founded) to any allowance from this country, were no greater than that of any, and every other officer of the French Army, who served in America the last war. To grant to one therefore, would open a wide door to applications of a similar nature, and to consequent embarrassments. Probably, the sum granted at the last session of Congress to the daughters of the Count de Grasse, has given rise to this application. That it has done so in other instances, I have good reasons to believe.

I am much pleased with the account you have given of the Succory. This, like all other things of the sort with me, since my absence from home, have come to nothing; for neither my Overseers nor Manager, will attend properly to anything but the crops they have usually cultivated: and in spite of all I can say, if there is the smallest discretionary power allowed them, they will fill the land with Indian Corn; altho’ they have a demonstrable proof, at every step they take, of its destructive effects. I am resolved however, as soon as it shall be in my power to attend a little more closely to my own concerns, to make this crop yield, in a great degree to other grain; to pulses, and to grasses. I am beginning again with Chiccory from a handful of seed given to me by Mr. Strickland; which, though flourishing at present has no appearance of seeding this year. Lucern has not succeeded better with me than with you; but I will give it another, and a fairer trial before it is abandoned altogether. Clover, when I can dress lots well, succeeds with me to my full expectation; but not on the fields in rotation; although I have been at much cost in seeding them. This has greatly disconcerted the system of rotation on which I had decided. I wish you may succeed in getting good seed of the winter Vetch: I have often imported it, but the seed never vegitated; or in so small a proportion as to be destroyed by weeds. I believe it would be an acquisition if it was once introduced properly in our farms. The Albany Pea, which is the same as the field Pea of Europe, I have tried, and found it grew well; but it is subject to the same bug that perforates the garden pea, and eats out the kernal; so it will happen, I fear, with the pea you propose to import. I had great expectation from a green dressing with Buck Wheat, as a preparatory fallow for a crop of Wheat; but it has not answered my expectation yet. I asscribe this however, more to mismanagement in the times of seeding and ploughing in, than to any defect in the system. The first ought to be so ordered, in point of time, as to meet a convenient season for ploughing it in while the plant is in its most succulent state; but this has never been done on my farms, and consequently has drawn as much from, as it has given to the earth. It has always appeared to me that there were two modes in which Buck Wheat might be used advantageously as a manure. One, to sow early; and as soon as a sufficiency of seed ripened to stock the ground a second time, to turn the whole in; and when the succeeding growth is getting in full bloom to turn that in also (before the seed begins to ripen): and when the fermentation and putrifaction ceases, to sow the ground in that state, and plough in the Wheat. The other mode is, to sow the Buck Wheat so late as that it shall be generally, about a foot high at the usual seeding of Wheat; then turn it in, and sow thereon immediately, as on a clover lay; harrowing in the seed lightly, to avoid disturbing the buried Buck Wheat. The last method I have never tried, but see no reason why it should not succeed. The other as I have observed before, I have practiced but the Buck Wheat has always stood too long, and consequently had become too dry and sticky, to answer the end of a succulant plant. But of all the improving and ameliorating crops, none, in my opinion, is equal to Potatoes on stiff, and hard bound land (as mine is). From a variety of instances I am satisfied that on such land, a crop of Potatoes is equal to an ordinary dressing. In no instance have I failed of good Wheat—Oats—or clover that followed Potatoes. And I conceit they give the soil a darker hue.

I shall thank you for the result of your proposed experiments relatively to the winter vetch and Pea, when they are made.

I am sorry to hear of the depredation committed by the Weavil in your parts. It is a great calamity at all times, and this year, when the demand for wheat is so great, and the price so high, must be a mortifying one to the farmer. The Rains have been very general, and more abundant since the first of August than ever happened in a summer within the memory of man. Scarcely a mill dam, or bridge between this and Philada. was able to resist them; and some were carried away a second, and even a third time.

Mrs. Washington is thankful for your kind remembrance of her, and unites with me in best wishes for you. With very great esteem & regard I am—Dear Sir Your Obedt. & affectionate

Geo: Washington

Mount Vernon 6th July 1796

That to your particular friends & connexions, you have described, and they have announced me, as a person under a dangerous influence; and that, if I would listen more to some other opinions all would be well. My answer invariably has been, that I had never discovered any thing in the conduct of Mr Jefferson to raise suspicions, in my mind, of his insincerity.

President John Adams

Auteuil August 27th 1784

He is an old Friend with whom I have often had Occasion to labour at many a knotty Problem, and in whose Abilities and Steadiness I always found great Cause to confide.

Quincy Summer 1811

I always loved Jefferson & still love him.

Quincy June 10, 1813

You may expect many more expostulations from one who has loved and esteemed you for Eight and thirty Years.

Quincy January 22, 1825

Our John [John Quincy Adams] has been too much worn to contend much longer with conflicting factions. I call him our John, because when you was at Cul de sac at Paris, he appeared to me to be almost as much your boy as mine, I have often speculated upon the consequences that would have ensued from my taking your advice, to send him to William and Mary College in Virginia for an Education.

Quincy April 19, 1825

I have lost your last letter to me, the most consolatory letter I ever received in my life, what would I not give for a copy of it—

Your friend to all eternity

John Adams

President James Madison

Montpellier, Feb 24, 1826.

You cannot look back to the long period of our private friendship & political harmony, with more affecting recollections than I do. If they are a source of pleasure to you, what ought they not to be to me? We cannot be deprived of the happy consciousness of the pure devotion to the public good with which we discharged the trusts committed to us. And I indulge a confidence that sufficient evidence will find its way to another generation, to ensure, after we are gone, whatever of justice may be withheld whilst we are here. The political horizon is already yielding in your case at least, the surest auguries of it. Wishing & hoping that you may yet live to increase the debt which our Country owes you, and to witness the increasing gratitude, which alone can pay it, I offer you the fullest return of affectionate assurances.

Montpellier, September, 1830.

In one of those scenes [in 1791], a dinner party at which we were both present, I recollect an incident now tho’ not perhaps adverted to then, which as it is characteristic of Mr. Jefferson, I will substitute for a more exact compliance with your request.

The new Constitution of the U. States having just been put into operation, forms of Government were the uppermost topics every where, more especially at a convivial board, and the question being started as to the best mode of providing the Executive chief, it was among other opinions, boldly advanced that a hereditary designation was preferable to any elective process that could be devised. At the close of an eloquent effusion against the agitations and animosities of a popular choice and in behalf of birth, as on the whole, affording even a better chance for a suitable head of the Government, Mr. Jefferson, with a smile remarked that he had heard of a university somewhere in which the Professorship of Mathematics was hereditary. The reply, received with acclamation, was a coup de grace to the Anti-Republican Heretic.

Montpr., April, 1831.

With Mr. Jefferson I was not acquainted till we met as members of the first Revolutionary Legislature of Virginia, in 1776. I had of course no personal knowledge of his early life. Of his public career, the records of his Country give ample information and of the general features of his character with much of his private habits, and of his peculiar opinions, his writings before the world to which additions are not improbable, are equally explanatory.

The obituary Eulogiums, multiplied by the Epoch & other coincidences of his death, are a field where some things not unworthy of notice may perhaps be gleaned. It may on the whole be truly said of him, that he was greatly eminent for the comprehensiveness & fertility of his genius, for the vast extent & rich variety of his acquirements; and particularly distinguished by the philosophic impress left on every subject which he touched.

Nor was he less distinguished for an early & uniform devotion to the cause of liberty, and systematic preference of a form of Govt. squared in the strictest degree to the equal rights of man. In the social & domestic spheres, he was a model of the virtues & manners which most adorn them.

President James Monroe

March 7, 1780

[Below was advice from James Monroe’s uncle Joseph Jones, a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses:]

I have no intimate acquaintance with Mr. Jefferson, but from the knowledge I have of him, he is in my opinion as proper a man as can be put into the office, having the requisites (ability, firmness and diligence). You will do well to cultivate his friendship, and cannot fail to entertain a grateful sense of the favors he has conferred upon you, and while you continue to deserve his esteem he will not withdraw his countenance. If, therefore, upon conferring with him upon the subject, he wishes or shows a desire that you go with him, I would gratify him. Should you remain to attend Mr. Wythe, I would do it with his approbation, and under the expectation that when you come to Richmond you shall hope for the continuance of his friendship and assistance. There is likelihood the campaign will this year be to the South, and in the course of it events may require the exertions of the militia of this State; in which case, should a considerable body be called for, I hope Mr. Jefferson will head them himself; and you no doubt will be ready cheerfully to give him your company and assistance, as well as to make some return of civility to him as to satisfy your own feelings of the common good.

September 6, 1782

For my part, till very lately, I have been a recluse. Chagrined at my disappointment with your State in not attaining the rank and command I ought, and chagrined at some disappointment in a private line. I retired from society with almost a resolution not to enter it again. Being fond of study I submitted the direction of my time and plan to my friend, Mr. Jefferson, one of our wisest and most virtuous republicans, and under his direction and indeed by his advice, I have hitherto till of late lived.

Washington July 5, 1815

With Mr Jefferson I had much friendly intercourse while in albemarle, and I am convincd of the interest which he takes in my welfare. The day he dined with us, he seemed anxious, that his disposition towards me should not be misunderstood, as he expressd such sentiments of my services, in the dept of war, to others, as left no doubt on that head. Heretofore he has been practic’d on by artful persons; but time & facts, the strongest of which has been my undeviating friendly deportment towards him, of which he has perhaps had more correct information of late, have put this in a true light. He is naturally frank & affectionate, and in my judgment, incapable of playing a double part. His enemies are never deceiv’d, by an improper confidence in his friendship. His whole family were kind to mine.

Charlestown May 2, 1819

In this place Mr. Jefferson was spoken of in reference to the acquisition of Louisiana. I spoke of him in terms, as strong as I could find, expressive of his extraordinary services to his country & great merit. Heretofore I could not find access to him but in connection with others. Of Genl. W. I could speak, because he stood on separate ground, and I could also speak of my immediate predecessor as such, but Mr. Jefferson was [hemm’d] in on both sides, and I could not touch him without censuring those who went before him. In this instance he stood alone, and I avail’d myself of the opportunity, to do him all possible justice, and disarm those who would turn him, or his name, against me, of the power of doing it with success. For generous acts there never can be self reproach; but in these cases, there has been exalted merit, for it is my candid opinion, that Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Madison have done more, since the establishment of the revolution (in which Genl. W. was preeminent) than any two persons on the continent. My great object is to bring the country together on just principles, and the course pursued, is I am satisfied, the most likely to succeed.

President John Quincy Adams

May 14, 1817

I am aware that by the experience of our history under the present constitution, Mr. Jefferson alone of our four Presidents has had the good fortune of a Cabinet harmonizing with each other and with him through the whole period of his administration. I know something of the difficulty of moving smoothly along with associates, equal in trust, justly confident of their abilities, disdainful of influence, yet eager to exercise it, impatient of control, and opposing real, stubborn resistance to surmises and phantoms of encroachment, and I see that in the nature of the thing an American President’s Cabinet must be composed of such materials.

June 21, 1822

When I see Mr. Jefferson, with the snows of fourscore winters upon his head and with all the claims of a life devoted to the service of his country and of mankind to the veneration of all, hunted in the face of evidence as a fraudulent peculator of a sum less than 1200 dollars by “a native of Virginia” with a malignity and pertinacity equal to but not surpassing the address and cunning of the accusation, I am willing to forget the charges equally false and equally base of the same native of Virginia against myself. That his charges against me are all as false as that against Mr. Jefferson I affirm, and have proved to the satisfaction of the Committee of Congress upon the expenditures in the Department of State.

January 4, 1824

In entertaining these sentiments it is certainly with all the regard and veneration due from me to Mr. Jefferson, as to one of the men to whom the nation owes its deepest debt of gratitude. I am charged by General Smyth with an attempt to ridicule Mr. Jefferson. An expression, distorted and misrepresented in the kennel newspapers of the present day, is the support which the General has for this accusation. Of that expression and of the cause from which it proceeded, I will not now speak. If the animosities of political contention are not to be eternal, it is time to consign that subject to silence. But I address you in the face of our common country, and I hope and trust this paper will pass under the eye of Mr. Jefferson himself.

July 7, 1826

There was a meeting of the members of the Administration, Mr. Southard having returned from his visit in Virginia. It was upon full consideration decided that there should be no proclamation upon the occasion of the decease of Mr. Jefferson; but I mentioned my opinion that it should be noticed in the next annual message to Congress; which was approved.

July 11, 1826

Executive Order

The General in Chief has received from the Department of War the following orders:

The President with deep regret announces to the Army that it has pleased the Disposer of All Human Events, in whose hands are the issues of life, to remove from the scene of earthly existence our illustrious and venerated fellow-citizen, Thomas Jefferson.

This dispensation of Divine Providence, afflicting to us, but the consummation of glory to him, occurred on the 4th of the present month--on the fiftieth anniversary of that Independence the Declaration of which, emanating from his mind, at once proclaimed the birth of a free nation and offered motives of hope and consolation to the whole family of man. Sharing in the grief which every heart must feel for so heavy and afflicting a public loss, and desirous to express his high sense of the vast debt of gratitude which is due to the virtues, talents, and ever-memorable services of the illustrious deceased, the President directs that funeral honors be paid to him at all the military stations, and that the officers of the Army wear crape on the left arm, by way of mourning, for six months.

Major-General Brown will give the necessary orders for carrying into effect the foregoing directions.

It has become the painful duty of the Secretary of War to announce to the Army the death of another distinguished and venerated citizen. John Adams departed this life on the 4th of this month. Like his compatriot Jefferson, he aided in drawing and ably supporting the Declaration of Independence. With a prophetic eye he looked through the impending difficulties of the Revolution and foretold with what demonstrations of joy the anniversary of the birth of American freedom would be hailed. He was permitted to behold the verification of his prophecy, and died, as did Jefferson, on the day of the jubilee.

A coincidence of circumstances so wonderful gives confidence to the belief that the patriotic efforts of these illustrious men were Heaven directed, and furnishes a new seal to the hope that the prosperity of these States is under the special protection of a kind Providence.

The Secretary of War directs that the same funeral honors be paid by the Army to the memory of the deceased as by the order of the 11th instant were directed to be paid to Thomas Jefferson, and the same token of mourning be worn.

Major-General Brown is charged with the execution of this order.

Never has it fallen to the lot of any commander to announce to an army such an event as now calls forth the mingled grief and astonishment of this Republic; never since History first wrote the record of time has one day thus mingled every triumphant with every tender emotion, and consecrated a nation's joy by blending it with the most sacred of sorrows. Yes, soldiers, in one day, almost in the same hour, have two of the Founders of the Republic, the Patriarchs of Liberty, closed their services to social man, after beholding them crowned with the richest and most unlimited success. United in their end as they had been in their highest aim, their toils completed, their hopes surpassed, their honors full, and the dearest wish of their bosoms gratified in death, they closed their eyes in patriot ecstasy, amidst the gratulations and thanksgivings of a people on all, on every individual, of whom they had conferred the best of all earthly benefits.

Such men need no trophies; they ask no splendid mausolea. We are their monuments; their mausolea is their country, and her growing prosperity the amaranthine wreath that Time shall place over their dust. Well may the Genius of the Republic mourn. If she turns her eyes in one direction, she beholds the hall where Jefferson wrote the charter of her rights; if in another, she sees the city where Adams kindled the fires of the Revolution. To no period of our history, to no department of our affairs, can she direct her views and not meet the multiplied memorials of her loss and of their glory.

At the grave of such men envy dies, and party animosity blushes while she quenches her fires. If Science and Philosophy lament their enthusiastic votary in the halls of Monticello, Philanthropy and Eloquence weep with no less reason in the retirement of Quincy. And when hereafter the stranger performing his pilgrimage to the land of freedom shall ask for the monument of Jefferson, his inquiring eye may be directed to the dome of that temple of learning, the university of his native State--the last labor of his untiring mind, the latest and the favorite gift of a patriot to his country.

Bereaved yet happy America! Mourning yet highly favored country! Too happy if every son whose loss shall demand thy tears can thus soothe thy sorrow by a legacy of fame.

The Army of the United States, devoted to the service of the country, and honoring all who are alike devoted, whether in the Cabinet or the field, will feel an honorable and a melancholy pride in obeying this order. Let the officers, then, wear the badge of mourning, the poor emblem of a sorrow which words can not express, but which freemen must ever feel while contemplating the graves of the venerated Fathers of the Republic.

Tuesday succeeding the arrival of this order at each military station shall be a day of rest.

The National flag shall wave at half-mast.

At early dawn thirteen guns shall be fired, and at intervals of thirty minutes between the rising and setting sun a single cannon will be discharged, and at the close of the day twenty-four rounds.

July 4, 1837

One lamentable evidence of deep degeneracy from the spirit of the Declaration of Independence is the countenance which has been occasionally given, in various parts of the Union, to this doctrine; but it is consolatory to know that, whenever it has been distinctly disclosed to the people, it has been rejected by them with pointed reprobation. It has, indeed, presented itself in its most malignant form in that portion of the Union the civil institutions of which are most infected by the gangrene of slavery. The inconsistency of the institution of domestic slavery with the principles of the Declaration of Independence was seen and lamented by all the Southern patriots of the Revolution; by no one with deeper and more unalterable conviction than by the author of the Declaration himself. No insincerity or hypocrisy can fairly be laid to their charge. Never, from their lips, was heard one syllable of attempt to justify the institution of slavery. They universally considered it as a reproach fastened upon them by the unnatural step-mother country; and they saw that, before the principles of the Declaration of Independence, slavery, in common with every other mode of oppression, was destined sooner or later to be banished from the earth. Such was the undoubting conviction of Jefferson to his dying day. In the memoir of his life, written at the age of seventy-seven, he gave to his countrymen the solemn and emphatic warning that the day was not distant when they must hear and adopt the general emancipation of their slaves. ‘Nothing is more certainly written,’ said he, ‘in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free.’

September 17, 1842

The utter and unqualified inconsistency of slavery, in any of its forms, with the principles of the North American Revolution, and the Declaration of our Independence, had so forcibly struck the Southern champions of our rights, that the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of slaves was a darling project of Thomas Jefferson from his first entrance into public life to the last years of his existence.

President Andrew Jackson

Washington City March 6th. 1825

Yesterday Mr Adams was inaugurated amidst a vast assemblage of citizens, having been escorted to the capitol with a pomp and ceremony of guns & drums not very consistent, in my humble opinion, with the character of the occasion. Twenty four years ago when Mr Jefferson was inducted into office no such machinery was called in to give solemnity to the occasion — he rode his own horse and hitched him him self to the enclosure. But it seems that times are changed — I hope it is not so with the principles that are to Characterise the administration of Justice and constitutional law. These in my fervent prayers for the prosperity and good of our country will remain unaltered, based upon the sovereignty of the people and adorned with no forms or ceremonies save those which their happiness and freedom shall command.

Nashville, July 26, 1826

I have been led here to make arrangements for paying the last respect due to the memory & manes of the sage of Monticello, the Father of Liberty, the patron of science, and the author of our declaration of Independence, who had the boldness by that instrument to declare to the despots of Europe in 1776, that we of right ought to be free, that all well organized governments are founded on the will of the people —established for their happiness and prosperity — This virtuous Patriot, Thos Jefferson is no more — he died on the 4th of July 10 minutes before one P.M. On yesterday when we met to make arrangements for this melancholy occasion the mail brought us the sad intelligence that another of the signers of the declaration of Independence was no more, that John Adams had departed this life also on the 4th of July at 6 o'clock P.M. Was well in the morning, heard the celebration, sickened at noon and died at 6 o'clock P.M. of the 4th inst. What a wonderful coincidence that the author and two signers of the declaration of Independence, two of the Ex-Presidents, should on the same day expire, a half a Century after that, that gave birth to a nation of freemen, and that Thos. Jefferson should have died the very hour of the day that the declaration of Independence was presented to and read in the Congress of 1776. Is this an omen that Divinity approbated the whole course of Mr. Jefferson and sent an angel down to take him from the earthly Tabernacle on this national Jubilee, at the same moment he had presented it to Congress and is the death of Mr. Adams a confirmation of the approbation of Divinity also, or is it an omen that his political example as President and adopted by his son, shall destroy this holy fabric created by the virtuous Jefferson.

May 27, 1830

In the Administration of Mr. Jefferson we have two examples of the exercise of the right of appropriation, which in the considerations that led to their adoption and in their effects upon the public mind have had a greater agency in marking the character of the power than any subsequent events. I allude to the payment of $15,000,000 for the purchase of Louisiana and to the original appropriation for the construction of the Cumberland road, the latter act deriving much weight from the acquiescence and approbation of three of the most powerful of the original members of the Confederacy, expressed through their respective legislatures.

December 6, 1836

However prevailing the restraint which veiled during the life of Mr. Madison this record of the creation of our Constitution, the grave, which has closed over all those who participated in its formation, has separated their acts from all that is personal to him or to them. His anxiety for their early publicity after this was removed may be inferred from his having them transcribed and revised by him self; and, it may be added, the known wishes of his illustrious friend Thomas Jefferson and other distinguished patriots, the important light they would shed to present as well as future usefulness, besides my desire to fulfill the pecuniary obligations imposed by his will, urged their appearance without awaiting the preparation of his other works, and early measures were accordingly adopted by me to ascertain from publishers in various parts of the Union the terms on which their publication could be effected.

It was also intended to publish with these debates those taken by him in the Congress of the Confederation in 1782, 1783, and 1787, of which he was then a member, and selections made by himself and prepared under his eye from his letters narrating the proceedings of that body during the periods of his service in it, prefixing the debates in 1776 on the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson so as to embody all the memorials in that shape known to exist. This expose of the situation of the country under the Confederation and the defects of the old system of government evidenced in the proceedings under it seem to convey such preceding information as should accompany the debates on the formation of the Constitution by which it was superseded.

President Martin Van Buren

Washington, May 29th, 1835

Thoroughly convinced that the overthrow of our present constitution and the consequent destruction of the confederacy which it binds together, would be the greatest sacrifice of human happiness and hopes that has ever been made at the shrine of personal ambition, I do not, hesitate to promise you, that every effort in my power, whether in public or private life, shall be made for their preservation. The father of his country, foreseeing this danger, warned us to cherish the union as the palladium of our safety; and the great exemplar of our political faith, Thomas Jefferson, has taught us, that to preserve that common sympathy between the states, out of which the union sprang, and which constitutes its surest foundation, we should exercise the powers which of right belong to the general government, in a spirit of moderation and brotherly love, and religiously abstain from the assumption of such as have not been delegated by the Constitution.

1854-1862

Earnestly engaged in a successful and lucrative practice, I had no desire to be a candidate for an elective office, nor did I become one until the Spring of 1812, when I was forced into that position by circumstances with which I could not deal differently. But from my boyhood I had been a zealous partisan, supporting with all my power the administrations of Jefferson and Madison…

Whilst this excitement was at its highest point I took a trip to Richmond, Virginia, and visited Spencer Roane whom I had never seen but long known, by reputation, as a hearty and bold Republican of the old School. I found him to my great regret on a bed of sickness, from which, although he lived some time, he never rose. But in all other respects he was the man I expected to meet — a root and branch Democrat, clear headed, honest hearted, and always able and ready to defend the right regardless of personal consequences. He caused his large form to be raised in his bed, and disregarding the remonstrances of his family he insisted in talking with me for several hours. He at once referred to the Albany Post Office Question, told me that he had read all the papers in the case and thought that we were perfectly right in the grounds we had assumed. He condemned in unqualified terms the course pursued by Mr. Monroe, spoke freely of past events in his career, and of his apprehensions that he would, if elected, be governed by the views he had avowed. Mr. Roane referred, with much earnestness, to the course of the Supreme Court, under the lead of Chief Justice Marshall, in undermining some of the most valuable clauses of the Constitution to support the pretensions of the Bank of the United States, and placed in my hands a series of papers upon the subject from the Richmond Enquirer, written by himself over the signature of Algernon Sidney. On taking my leave of him I referred to the manner in which he had arranged the busts of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe in his room, and said that if there had been anything of the courtier in his character he would have placed Mr. Monroe, he being the actual President, at the head instead of the foot. He replied with emphasis, "No ! No ! No man ranks before Tom Jefferson in my house ! They stand Sir, in the order of my confidence and of my affection.”…

They were wise and experienced men and knew that such a subject could not be trusted to professions or acts which would be open to different constructions, and could only be safely dealt with by such measures as must carry conviction to the most prejudiced minds because they went directly to the accomplishment of their object. From such considerations and from such sources issued the Act of July 1787 for the government of the North Western Territory. By this Memorable Act its author and supporters intended not only to provide effectually for the peace and safety of their beloved country, but to repel, as far as was in their power, the suspicion of their fidelity to the cause of freedom which their enemies had attempted to fix upon them. Whether we regard the source from which it originated, the support it received on its passage, or its efficiency in promoting the great object of its enactment, this Law deserves a place in our National Archives side by side with the Declaration of Independence and the Federal Constitution, Attempts have been made to deprive Mr. Jefferson of the credit of this great measure, as there have been cavillers against every truth of history however firmly established. Nothing can be more certain than that it was to his master mind that the country is indebted for its conception, and to his perseverance in its support seconded by the Legislature of Virginia and the old Congress for its completion…

I firmly believe that if Mr. Jefferson had thought it practicable to acquire the territory and to obtain its admission as a State without such stipulations, he would have made the attempt. His whole course upon the subject of slavery warrants this opinion…

My feelings were of a very different character. My earliest political recollections were those of the day when I exulted at the election of Mr. Jefferson, as the triumph of a good cause over an Administration and Party, who were as I thought subverting the principles upon which the Revolution was founded and fastening upon the Country a system which tho' different in form was nevertheless animated by a policy in the acquisition and use of political power akin to that which our ancestors had overthrown. I had ever since regarded the continued success of Mr. Jefferson's policy as the result of the superiority of the principles he introduced into the administration of the Government over those of his predecessor, and was sincerely desirous that they should continue to prevail in the Federal Councils…

On the next and subsequent days, leaving the Governor to be entertained by our host's grand-daughter, an accomplished and very agreeable young lady, now Mrs. Coolidge, of Boston, (whose future husband paid his first visit to her while we were at Monticello) we employed our mornings in drives about the neighbourhood, during which it may well be imagined with how much satisfaction I listened to Mr. Jefferson's conversation. His imposing appearance as he sat uncovered — never wearing his hat except when he left the carriage and often not then — and the earnest and impressive manner in which he spoke of men and things, are yet as fresh in my recollection as if they were experiences of yesterday. I have often reproached myself for having omitted to make memoranda of his original and always forcible observations and never more than at the present moment. Uppermost in my mind is the recollection of his exemption from the slightest remains, of party or personal prejudice against those from whom he had differed during the stormy period of his public life. Those who like myself had an opportunity to witness his remarkable freedom from the common reproach of political differences would find it difficult to doubt the sincerity of the liberal views he expressed in his Inaugural Address in regard to parties and partisan contests…

I derived the highest gratification from observing that [Mr. Jefferson’s] devotion to the public interest, tho' an octogenarian and oppressed by private griefs, was as ardent as it had been in his palmiest days. Standing upon the very brink of the grave, and forever excluded from any interest in the management of public concerns that was not common to all his fellow citizens, he seemed never to tire in his review of the past and in explanations of the grounds of his apprehensions for the future, both obviously for my benefit. In relation to himself he was very reserved — taking only the slightest allowable notice of his agency in the transactions of which he spoke. Happening to notice a volume in his library labelled curtly and emphatically — "Libels" — I opened it and found its contents to consist entirely of articles abusive of himself, cut out of the Newspapers; and shewing it to him he laughed heartily over the brochure and said that it had been his good fortune thro' life to be, in an unusual degree, indifferent to the groundless attacks to which public men were exposed. My inquiries in regard to individuals who had been prominent actors on the political stage in his day, were naturally as frequent as was consistent with propriety, and his replies were prompt and made with apparent sincerity and absolute fairness. Of Gen. Washington and of his memory he invariable spoke with undisguised regard and reverence…

Observing that in describing party movements he almost always said 'The republicans" pursued this course, and "Hamilton" that — not naming the federalists as a party, except by the designation of a sole representative, I brought this peculiarity to his attention. He said it was a habit that he had fallen into at an early period from regarding almost every party demonstration during the administrations preceding his own, as coming directly, or indirectly from Hamilton. He spoke of him frequently and always without prejudice or ill will, regarding him as a man of generous feelings and sincere in his political opinions. In answer to my question whether Hamilton participated in some step that he condemned, he replied — "No ! He was above such things !" His political principles Mr. Jefferson condemned without reserve, save only their sincerity, regarding them in their tendency and effects as more anti-republican than those of any of his contemporaries…

Those better regulated minds, however, whose gratification on reaching that high office is mainly derived from the consciousness that their countrymen have deemed them worthy of it and from the hope that they may be able to justify that confidence and to discharge its duties so as to promote the public good, will save themselves from great disappointments by postponing all thoughts of individual enjoyment to the completion of their labors. If those whose sense of duty and whose dispositions are of the character which alone can fit them for that station look to secure much personal gratification while swaying the rod of power they will find in that as in all other human calculations and plans "begun on earth below,'' that

”The ample proposition that hope makes

Fails in the promised largeness.”

At the very head of their disappointments will stand those inseparable from the distribution of patronage, that power so dazzling to the expectant dispenser, apparently so easily performed and so fruitful of reciprocal gratification. Whatever hopes they may indulge that their cases will prove an exception to the general rule they will find, in the end, their own experience truly described by Mr. Jefferson when he said that the two happiest days of his life were those of his entrance upon his office and of his surrender of it. The truth of the matter may be stated in a word: whilst to have been deemed worthy by a majority of the People of the United States to fill the office of Chief Magistrate of the Republic is an honor which ought to satisfy the aspirations of the most ambitious citizen, the period of his actual possession of its powers and performance of its duties is and must, from the nature of things, always be, to a right minded man one of toilsome and anxious probation.

President William Henry Harrison

August 6, 1802

When I had the honour to see you [Thomas Jefferson] in Philadelphia in the Spring of the year 1800 you were pleased to recommend to me a plan for a Town which you supposed would exempt its inhabitants in a great degree from those dreadful pestilences which have become so common in the large cities of the United States. As the laws of this Territory have given to the Governor the power to designate the seats of Justice for the Counties, and as the choice of the Citizens of Clark County was fixed upon a spot where there had been no town laid out, I had an opportunity at once of gratifying them—of paying respect to your recommendation, and of conforming to my own inclinations—The proprietor of the land having acceded to my proposals a Town has been laid out with each alternate square to remain vacant forever (excepting one Range of squares upon the River)—and I have taken the liberty to call it Jeffersonville—The beauty of the spot on which the Town is laid out, the advantages of the situation (being just above the Rapids of the Ohio) and the excellence of the plan, makes it highly probable that it will at some period not very remote become a place of considerable consequence—At the sale of the lots a few days ago several of them were struck off at 200 Dollars. It is in contemplation to cut a canal round the Rapids on this side—a project which it is said can be very easily executed and which will be highly beneficial to the Town. Indeed I have very little doubt of its flourishing. It is my ardent wish that it may become worthy of the name it bears, and that the Humane & benevolent views which dictated the plan may be reallised—

If Sir it should again happen that in the wide Range which you suffer your thoughts to take for the benefit of Mankind—the accomplishment of any of your wishes can in the smallest degree be aided by me—I beg you to believe that your commands shall be executed to the utmost extent of my small talent.

March 4, 1841

I proceed to state in as summary a manner as I can my opinion of the sources of the evils which have been so extensively complained of and the correctives which may be applied. Some of the former are unquestionably to be found in the defects of the Constitution; others, in my judgment, are attributable to a misconstruction of some of its provisions. Of the former is the eligibility of the same individual to a second term of the Presidency. The sagacious mind of Mr. Jefferson early saw and lamented this error, and attempts have been made, hitherto without success, to apply the amendatory power of the States to its correction…

The influence of the Executive in controlling the freedom of the elective franchise through the medium of the public officers can be effectually checked by renewing the prohibition published by Mr. Jefferson forbidding their interference in elections further than giving their own votes, and their own independence secured by an assurance of perfect immunity in exercising this sacred privilege of freemen under the dictates of their own unbiased judgments…

All the influence that I possess shall be exerted to prevent the formation at least of an Executive party in the halls of the legislative body. I wish for the support of no member of that body to any measure of mine that does not satisfy his judgment and his sense of duty to those from whom he holds his appointment, nor any confidence in advance from the people but that asked for by Mr. Jefferson, "to give firmness and effect to the legal administration of their affairs."

President John Tyler

July 6, 1826

Whereas it is made known to the Executive Department that Thomas Jefferson, the distinguished benefactor to his Country, departed this life on the 4th inst. — and this Department being impressed with a deep sense of the great loss which Virginia, the Union and the world at large have sustained in the death of this Philosopher, Statesman, Patriot, and Philanthropist — and whereas a sense of what we owe to the present, and all future generations, and not merely a regard to our own feelings, which of themselves would prompt us to the measure, requires at the hands of this Department a manifestation by all means in its power of respect for the memory of one whose whole life has been passed in unceasing devotion to the advancement of human happiness, and the establishment of Liberty on a sure and lasting foundation.

Inspired by these sentiments, and impressed with the regret which the occasion is so well calculated to produce, we, the Governor and Council of the State of Virginia, do resolve as follows:

1. That the Hall of the House of Delegates, the Senate Chamber, and the Executive Chamber be hung in mourning together with the main entrances to the Capitol.

2. That the Bell in the Guard house be tolled through the day.

July 11, 1826

EULOGY FOR THOMAS JEFFERSON

Why this numerous assemblage; this solemn and melancholy procession; these habiliments of woe? Do they betoken the fall of some mighty autocrat, of some imperial master who hath “bestrid the earth like a Colossus” and whose remains are followed to the grave by the tools and minions of his power? Are they the tokens of a ceremonious woe, a mere mockery of feeling? Or are they the spontaneous offerings of gratitude and love? What mighty man has fallen in Israel, and why has Virginia clothed herself in mourning? The tolling of yon dismal bell, and the loud but solemn discharge of artillery, hath announced to the nation the melancholy tidings — THOMAS JEFFERSON no longer lives! That glorious orb which has for so many years given light to our footsteps has set in death. The patriot, the statesman, the philosopher, the philanthropist, has sunk into the grave. Virginia mourns over his remains, and her harp is hung upon the willows.

Why need I say more? There is a language in this spectacle which speaks more eloquence than tongue can utter. This is the testimony of a well-spent life; the tribute of a nation's gratitude. Look on this sight, ye rulers of the earth, and learn from it lessons of wisdom. Ye ambitious and untamed spirits, who seek the attainment of glory by a scaffolding formed of human suffering, behold a people in tears over the funeral, bier of their benefactor; and if true glory be your object, profit by this example. In pronouncing the eulogy of the dead, my countrymen, I have no blood stained banners to present; no battles to recount; no sword or helmet to deposit on his hearse. I have to entwine a civic wreath which philosophy has woven and patriotism hallowed. The achievements of the warrior in the field attract the attention of mankind, and fasten on the memory, while the labors of the civilian too often pass unnoted and unknown. But not so with that man whose death we this day mourn. The results of his policy are exhibited in all around. Although his sun has sunk below the horizon of this world, yet hath it left a train of light, which shall never be extinguished.

At the commencement of his successful career, he manifested the same devotion to the rights of man which he evinced in all his after life. At an early day he so distinguished himself as the firm and fearless asserter of the rights of colonial America, as to draw upon him the frown of the royal governor, and had already anticipated the occurrence of the period when the colonies should be elevated to the condition of free, sovereign, and independent States. Having drawn his principles from the fountains of a pure philosophy, he was prepared to assail the slavish doctrine that man was incapable of self-government, and to aid in building up on its overthrow that happy system under which it is our destiny to live.

On the coming of that tremendous storm, which for eight years desolated our country, Mr. Jefferson hesitated not, halted not. Born to rich inheritance, destined to the attainment of high distinction under the regal government, courted by the aristocracy of the land, he adventured, with the single motive of advancing the cause of his country and of human freedom, into that perilous contest, throwing into the scale his life and fortune, as if of no value. The devoted friend of man, he had studied his rights in the great volume of nature, and saw with rapture the era at hand when those rights should be proclaimed, and the world aroused from the slumber of centuries. The season was approaching for the extension of the empire of reason and philosophy, and the disciple of Locke and Sidney rejoiced at its approach. Among his fellow-laborers, — those devoted champions of liberty, — those brilliant lights which shall forever burn, he stood conspicuous.

But how transcendently bright was that halo of glory by which he was surrounded on the fourth of July, 1776! Oh, day ever precious in the recollections of freemen! now rendered doubly so by the recollection that it was the birthday of a nation, and the last of him who had conferred on it immortality. Yes, illustrious man, it was given thee to live until the advent of a nation's jubilee. Thy disembodied spirit was then upborne by the blessings of ten millions of freemen, and the day and hour of thy renown was the day and hour of thy dissolution. How inseparable is now the connection between that glorious epoch and this distinguished citizen!

Does there not seem to have been an especial providence in his death? The sun of that day rose upon him, and the roar of artillery and the hosannas of a nation sounded into his ears the assurances of his immortality. So precious a life required a death so glorious. Who now shall set limits to his fame? On the annual recurrence of that glorious day, when with pious ardor millions yet unborn shall breathe the sentiments contained in the celebrated Declaration of Independence, — when the fires of liberty shall be kindled on every hill and shall blaze in every vale, shall not the name of Jefferson be pronounced by every lip and written on every heart? Shall not the rejoicing of that day, and the recollection of his death, cause the smile to chase away the tear, and the tear to becloud the smile?

But not to the future millions of these happy States shall his fame be confined. That celebrated state paper will be found wherever is found the abode of civilized man. Sounded in the ears of tyrants, they shall tremble on their thrones, while man, so long the victim of oppression, awakes from the sleep of ages and bursts his chains. The day is rapidly approaching, a prophetic tongue has pronounced it "to some nations sooner, to others later, but finally to all," when it will be made manifest "that the mass of mankind have not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God." Already has this truth aroused the one-half of this continent from the lethargy in which it has so long reposed. Already are the pagans of liberty chanted from the Gulf of Mexico to the Rio de la Plata, and its altars are erecting on the ruins of a superstitious idolatry.

A mighty spirit walks abroad upon the earth, which shall, in its onward march, over turn principalities and powers, and trample thrones in the dust. And when the happy era shall arrive for the emancipation of nations, hastened on as it will be by the example of America, shall they not resort to the Declaration of our Independence as the charter of their rights, and will not its author be hailed as the benefactor of the redeemed? But, my countrymen, this state paper is not the only lasting testimonial which he has left us of his devotion to the rights of man.

Where should I stop were I to recount the multiplied and various acts of his life, all directed to the security of those rights? The statute-book of this State, almost all that is wise in policy or sanctified by justice, bears the impress of his genius, and furnishes evidence of that devotion.

But I choose to present him as a mighty reformer. He was born to overturn systems and to pull down establishments. He had a more difficult task to accomplish than the warrior in the embattled field. He had to conquer man, and bring him to a true sense of his own dignity. He had to encounter prejudices become venerable by ager to assail error in its strong places, and to expel it even from its fastnesses. He advanced to the charge with a bold and reckless intrepidity, but with a calculating coolness.

The Declaration, of which I have just spoken, had announced the great truth that man was capable of self-government, but it still remained for him to achieve a conquest over an error which was sanctified by age and fortified by the prejudices of mankind. He dared to proclaim the important truths, — "that Almighty God hath created the mind free; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the Holy Author of our religion, who, being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in His almighty power to do; that the impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical, who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men, have assumed dominion over the faith of others setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and in fallible, and, as such, endeavoring to impose them on others, have established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world, and through all time;" — “that truth is great and will prevail, if left to herself; that she is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error, and has nothing to fear from the conflict, unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons — free argument and debate; errors ceasing to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them."

This is the language of the bill establishing religious freedom, and is to be found on our statute-book. How solemn and sublime, and how transcendently important are the truths which it announces to the world. What but his great and powerful genius could have contemplated the breaking asunder those bonds in which the conscience had been bound for centuries? Who but the ardent and devoted friend of man would have exposed himself to the thunders and denunciations of the church throughout all Christendom, by breaking into its very sanctuary, and dissolving its connection with government? If he consulted the page of history, he found that the church establishment, exercising unlimited control over the conscience, and unlocking at its pleasure the very gates of heaven to the faithful devotee, had, in all ages, governed the world; that kings had been made by its thunders to tremble on their thrones, and that thrones had been shivered by the lightnings of its wrath. In casting his eyes over the face of the globe, he beheld, it is true, the mighty spirit of Protestantism walking on the waters, but confined and limited in its empire, and even its garments dyed in the blood of the martyr. Over the rest of the world he beheld the religion of the blessed Redeemer converted into a superstitious rite, and locked up in a gloomy and ferocious mystery. The sentence of the terrible inquisitor sounded in his ears, followed by the clank of chains and the groans of the victim. If he looked in the direction from whence the sound proceeded, he saw the fires of the auto de fe consuming the agonized body of the offender, and thus finishing the last act of this horrible tragedy. He felt the full force of this picture, and, regardless of all personal danger, set about the accomplishment of the noble purpose of setting free the mind.

He, who had so much contributed to the unbinding of the hands of his countrymen, would have left his work unfinished if he had not also unfettered their consciences. True, he had in all this great work able coadjutors, who, like himself, had adventured all for their country; but he was the great captain who arrayed the forces and directed the assault. Let it, then, be henceforth proclaimed to the world, that man's conscience was created free; that he is no longer accountable to his fellow-man for his religious opinions, being responsible therefor only to his God; that it is impious in mortal man, whether clothed in purple or in lawn, to assume the judgment-seat; and that the connection between church and state is an unholy alliance, and the fruitful source of slavery and oppression; and let it be dissolved.

What an imperishable monument has Mr. Jefferson thus reared to his memory, and how strong are its claims to our gratitude! When from every part of this extended Republic the prayers and thanksgiving of countless thousands shall ascend to the throne of grace, each bending at his own altar, and worshiping his Creator after his own way, shall not every lip 'breathe a blessing on his name, and every tongue speak forth his praise? Yes, he was born a blessing to his country, and in the fulness of time shall become a blessing to mankind. He was, indeed, a precious gift — a most beloved reformer. Shall we not, then, while weeping over his loss, offer thanks to the Giver of every perfect gift for having permitted him to live?

But, my countrymen, we have still further reason for the deepest gratitude. He had not yet finished his memorable efforts in the cause of human liberty. The temple had been reared, but it was exposed to violent assaults from without. Those principles which in former ages had defeated the hopes of man, and had overthrown republics, remained to be hunted out, exposed, and guarded against. The most powerful of these was the concentration and perpetuation of wealth in the hands of particular families, and the creation thereby of an overweening aristocracy. The fatal influence of this principle had been felt in all ages and in all countries. The feeling of pride and haughtiness which wealth is so well calculated to engender, and the homage which mankind are unhappily so much disposed to render it, cause the perpetuation of large fortunes in the hands of families, the most fearful antagonist to human liberty. Marcus Crassus has said, that the man who aspires to rule a republic should not be content until he has mastered wealth sufficient to maintain an army; and Julius Caesar paved the way to the overthrow of Roman liberty by the unsparing distribution, from his inexhaustible stores, of largesses to the people.

Mr. Jefferson saw, therefore, the great necessity for reformation in our municipal code, and the act abolishing entails, and that regulating descents, are, in all their essential features, the offsprings of his well-constituted intellect. He has acted throughout on the great principle of the equality of mankind, and his every effort has been directed to the preservation of that equality among his countrymen. How powerful in its operation is our descent law in producing this effect! Founded on the everlasting principles of justice, it distributes among all his children the fruits of the parent's labor. The first-born is no longer considered the chosen of the Lord;. but nature asserts her rights, and raises the last to an equality with the first. Thus it is that the spirit of a proud independence, so auspicious to the durability of our institutions, is engendered in the bosom of our citizens; thus it is that we are under the influence of an agrarian law in effect, while nature, instead of being suppressed, is excited by new stimuli. The great law-giver of Sparta in vain sought to perpetuate the great principle of equality among the then renowned republic by various measures, all of which ultimately failed; but there is a measure which cannot fail — a measure which depends, not upon the veneration of the character of any one man, but lays hold of the affections, and records its own perpetuity in the great volume of nature — one without which the blood shed in the Revolution would have been shed in vain — without which the glories of that struggle would fade away, or exist but as another proof of man's incapacity for self-government.

What more shall I say of it? May I not call it that great measure which, to our political, like the sun to our planetary, system, imparts light and heat, unveils all its beauties, and manifests its strength? Tell me, then, ye destinies that control the future, say, is not this man's fame inscribed in adamant? Say, men of the present age, ye lovers of liberty, ye shining lights from amid the gloom of the world, say, does Virginia claim too much when she pronounces her Jefferson wiser than the law-givers of antiquity? Tell me, then, men of America, have ye not lost your father, your benefactor, your best friend? And you, the men of other countries, where the light of his example is now dimly seen — you who constitute the salt of the earth, will you not kindle your lamps in the mighty blaze of his flame, and distribute the blessings of his existence around you? Here, then, I might stop. The cause of this mournful procession is explained; his claim to the gratitude of mankind is made manifest, and his title to immortality is established. But his labors did not here cease; I have still to exhibit him to you in other lights than those in which we have already regarded him — to present other claims to your veneration and gratitude. Passing over those incidents which history has already recorded, let us regard him while in that station which I now fill, more by the kindness of the public than from any merit of my own.

We here recognize in him the able vindicator of insulted America against the sarcasms of European philosophy. Indulging in the visions of fallacious theory, it was attempted to be proved that the flush and glow which nature assumed on the other side of the Atlantic was converted on this continent into the cadaverous aspect of disease and degeneracy; that while she walked abroad over the face of Europe in all her beautiful proportions, here she hobbled on crutches and degenerated into a dwarf. How successfully he threw back this slander upon our calumniators, let the world decide.

His Notes on Virginia will ever bear him faithful witness. Slanders upon nations make the deepest and most lasting impressions. They fall not on one man, but on a whole people, and if not refuted, tend to sink them in the scale of existence. If under any circumstances they are to be deprecated, how much more are they to be so when published against a nation not even in the gristle of manhood, unknown to the mass of mankind, and struggling to be free? Such was the condition of America at that day. Shut out from free intercourse with Europe by the monopolizing spirit of the parent state, she had remained unknown to the world, and was regarded as an ex tensive wild, within whose bosom the fires of genius and intellect had not as yet been kindled. Mr. Jefferson saw then the injury she would sustain, if these slanders remained unrefuted. Vigilant at his post, and guardful of the interests of the States, he encountered the most distinguished of the philosophers of Europe, and his victory was complete.

It was answer enough for him to have said, what in substance he did say, that in war we had produced a Washington, in physics a Franklin, and in astronomy a Rittenhouse; and if his triumph had not been esteemed complete, might we not add, with the certainty of success, that in philosophy and politics she had produced a Jefferson? In all the several stations which he afterward filled, we find him laboring unceasingly for the good of his country.

Having won by his virtues and talents the confidence of Washington, he was called to preside over the Department of State. In this station he vindicated the rights of America against the sophistry of European cabinets, and gave proof of that skill in diplomacy for which he will be distinguished through all future ages. When the future statesman shall look for a model from which to form his style of diplomatic writing, will he not cease his search and seize with avidity on that, the offspring of the secretary's pen, in his correspondence with Hamilton and Genet?

Called, at length, by the voice of the people, to the presidency of these United States, he furnished the model of an administration conducted on the purest principles of republicanism. He sought not to enlarge his powers by construction, but, referring everything to his conscience, made that the standard of the constitutional interpretation. Regarding the government in its true -and beautiful light of a confederation of States, he could not be drawn from his course by any of those splendid conceptions which shine but to mislead. He extinguished $33,000,000 of the national debt; enlarged the boundaries of our territorial jurisdiction, by the addition of regions more extensive than our original possessions; overawed the Barbary powers; and preserved the peace of the nation amid the tremendous convulsions which then agitated the world.

I will dwell no longer on this fruitful topic, nor indulge my feelings. Party spirit is buried in his grave, and I will not disinter it. The American people will, as one man, look with admiration on his character, and dwell with affectionate delight over those bright incidents in his life to which I have already alluded. Thus, then, my countrymen, in the sixty-ninth year of his age, he terminated his political career, and went into the shades of retirement at Monticello. But, unlike the politicians of other days, who had fled from the cares and anxieties of public life, that retirement was not inglorious. He still lived for his country and the world. Let that beautiful building devoted to the sciences, the last of his labors, reared under his auspices, and cherished by his care, testify to this. How choice and how delightful this, the last fruit of his bearing! How lasting a monument will it be to his memory! It will be, we may fondly hope, the perpetual nursery of those great principles which it was the business of his life to inculcate. The youth of Virginia, and the youth of our sister States, to use his own beautiful language, “will bring hither their genius to be kindled at our fire." "The good Old Dominion, the blessed mother of us all, will then raise her head with pride among the nations."

When history shall, at some future day, come to draw his character, to what department shall she assign him? Shall she encircle his brow with the wreath of civic worth? Or shall philosophy weave a garland of her own? He is equally dear to all the sciences. In mournful procession they have re paired to the tomb where his mortal remains are inurned, and hallowed the spot. Yes, hallowed be the spot where he rests from his labors. Wave after wave may roll by, sweeping in its resistless course countless generations from the earth; yet shall the resting-place of Jefferson be hallowed. Like Mount Vernon, Monticello shall catch the eye of the wayfarer and arrest his course. 'There shall he draw the inspiration of liberty, and learn those great truths which nature destined him to know.

Is not, then, this man's life most beautifully consistent? Trace him from the period of his earliest manhood to the hour of his final dissolution, and does not his ardor in the prosecution of the great work of human rights excite your admiration and enlist your gratitude? May it not be said that he has lived only for the good of others? Look upon him in the last stages of his existence. But a few days before his death he exults in the happiness of his country and the full confirmation of his labors. With the prospect of death before him, suffering under a cruel disease, he offers up an impressive prayer for the good of mankind. When speaking of the then approaching jubilee, in writing to the Mayor of Washington, he says: “May it be to the world — what I believe it will be — the signal for arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition have persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings of free government." And it shall be that signal. A flood of light has burst upon the world, and the juggernauts of superstition and the gloom of ignorance shall melt before its brightness.

Will you look upon him, my countrymen, in the latest moment of his existence? Shall I make known to you his fond concern for you and your posterity, when the hand of death pressed heavily upon him? Learn, then, that he dwelt on the subject of the University — portrayed the blessings which it was destined to diffuse, and, forgetful of his valuable services, often urged his physician to leave his bedside, lest his class might suffer in his absence. One other theme dwelt on his lips until they were motionless. It was the fourth of July. On the fourth, so says my correspondent, he raised his languid head and said, “This is the fourth of July," and the smile of contentment played upon his lips. Heaven heard his prayers, and crowned his wishes. Oh, precious life! Oh, glorious death! He has left us, my countrymen, a previous legacy. His last words were, “I resign myself to my God, and my child to my country." And shall not that child of his old age — that only surviving daughter, the solace of his dying hour — be fostered and cherished by a grateful country? Thus has terminated, in the eighty-fourth year of his age, the life of one of the greatest and best of men. His “weary sun hath made a golden set."

Let the rulers of the nations profit by his example — an example which points the way to the temple of true glory, and proclaims to the statesman of every age and of every tongue, —

“Be just, and fear not;

“Let all the ends thou aimest at be thy country's;

“Thy God's, and Truth;

“Then shall thy lifeless body sleep in blessings, and the tears of a nation water thy grave.

“Let his life be an instructive lesson to us, my countrymen. Let us teach our children to reverence his name, and even in infancy to lisp his principles. As one great means of perpetuating freedom, let the recurrence of the day of our nation's birth be ever hailed with rapture. Is it not stamped with the seal of divinity? How wonderful are the means by which He rules the world! Scarcely has the funeral knell of our Jefferson been sounded in our ears, when we are startled by the death-bell of another patriot, his zealous co adjutor in the holy cause of the Revolution — one among the foremost of those who sought his country's disenthralment — of Adams, the compeer of his early fame, the opposing orb of his meridian, the friend of his old age, and his companion to the realms of bliss. They have sunk together in death, and have fallen on the same glorious day into that sleep which knows no waking. Let not party spirit break the rest of their slumbers, but let us hallow their memory for the good deeds they have done, and implore that God who rules the universe to smile on our country.”

October 27, 1836

Upon retiring from the Senate and looking into my private affairs, I found them in such utter disorder as to require my unremitting and undivided attention. Hence I have been closely at home all the summer and fall. In this I have but shared the fate of all others who like myself have made themselves a voluntary sacrifice to public service for the entire period of their manhood. My political opponents (enemies I will not call them) are therefore entitled to my thanks for having allowed me a fit season to put my house in order. Do not believe for a moment, however, that I have been a listless observer of passing events. On the contrary, when I have seen a President descend from the lofty eminence of being the representative of a great confederacy to enter the dirty arena of politics and throw himself forward as the most prominent advocate of one of the aspirants to the succession, and then have the affrontery to breathe the name of Jefferson, I have asked myself if it were possible that the Virginia people could pocket the insult thus offered to their understanding.

President James Polk

April 30, 1846

I told him I had no personal feeling in relation to these nominations except as to one or two of them, and that I wished him to understand that I did not desire to influence his course in regard to them contrary to his judgment. I told him however that Northern men attached more importance to appointments than Southern men did and that if Southern Senators undertook to defeat nominations in the North made on the recommendation of Northern Senators it would excite them, and impair if not destroy my power to be useful in effecting the passage of the Bill to reduce the tariff and the Constitutional Treasury Bill. I reminded him that Mr. Jefferson's plan was to conciliate the North by the dispensation of his patronage, and to rely on the South to support his principles for the sake of these principles.

August 4, 1846

Two precedents for such a proceeding exist in our past history, during the Administration of Mr. Jefferson, to which I would call your attention. On the 26th February, 1803, Congress passed an act appropriating $2,000,000 "for the purpose of defraying any extraordinary expenses which may be incurred in the intercourse between the United States and foreign nations," "to be applied under the direction of the President of the United States, who shall cause an account of the expenditure thereof to be laid before Congress as soon as may be;" and on the 13th February, 1806, an appropriation was made of the same amount and in the same terms. The object in the first case was to enable the President to obtain the cession of Louisiana, and in the second that of the Florida. In neither case was the money actually drawn from the Treasury, and I should hope that the result might be similar in this respect on the present occasion, though the appropriation is deemed expedient as a precautionary measure.

August 8, 1846

Mr. Jefferson, who was fully cognizant of the early dissensions between the Governments of the United States and France, out of which the claims arose, in his annual message in 1808 adverted to the large surplus then in the Treasury and its "probable accumulation," and inquired whether it should "lie unproductive in the public vaults;" and yet these claims, though then before Congress, were not recognized or paid. Since that time the public debt of the Revolution and of the War of 1812 has been extinguished, and at several periods since the Treasury has been in possession of large surpluses over the demands upon it. In 1836 the surplus amounted to many millions of dollars, and, for want of proper objects to which to apply it, it was directed by Congress to be deposited with the States.

December 15, 1847

President Jefferson, in his message to Congress in [December 2,] 1806 [Sixth Annual Message], recommended an amendment of the Constitution, with a view to apply an anticipated surplus in the Treasury "to the great purposes of the public education, roads, rivers, canals, and such other objects of public improvement as it may be thought proper to add to the constitutional enumeration of Federal powers." And he adds:

“I suppose an amendment to the Constitution, by consent of the States, necessary, because the objects now recommended are not among those enumerated in the Constitution, and to which it permits the public moneys to be applied.”

In 1825 he repeated, in his published letters, the opinion that no such power has been conferred upon Congress.

[Below is from the editor of The Diary of James K. Polk, Milo Milton Quaife:]

To this quality of Industry must be added Polk's high reputation for consistency as a party man. Early In his public career he made Thomas Jefferson his political polestar and throughout his career adhered to the principles of the founder of the Republican party with unswerving fidelity; and the knowledge of this fidelity operated to strengthen his control over his followers in the years when he was the official head of his party.

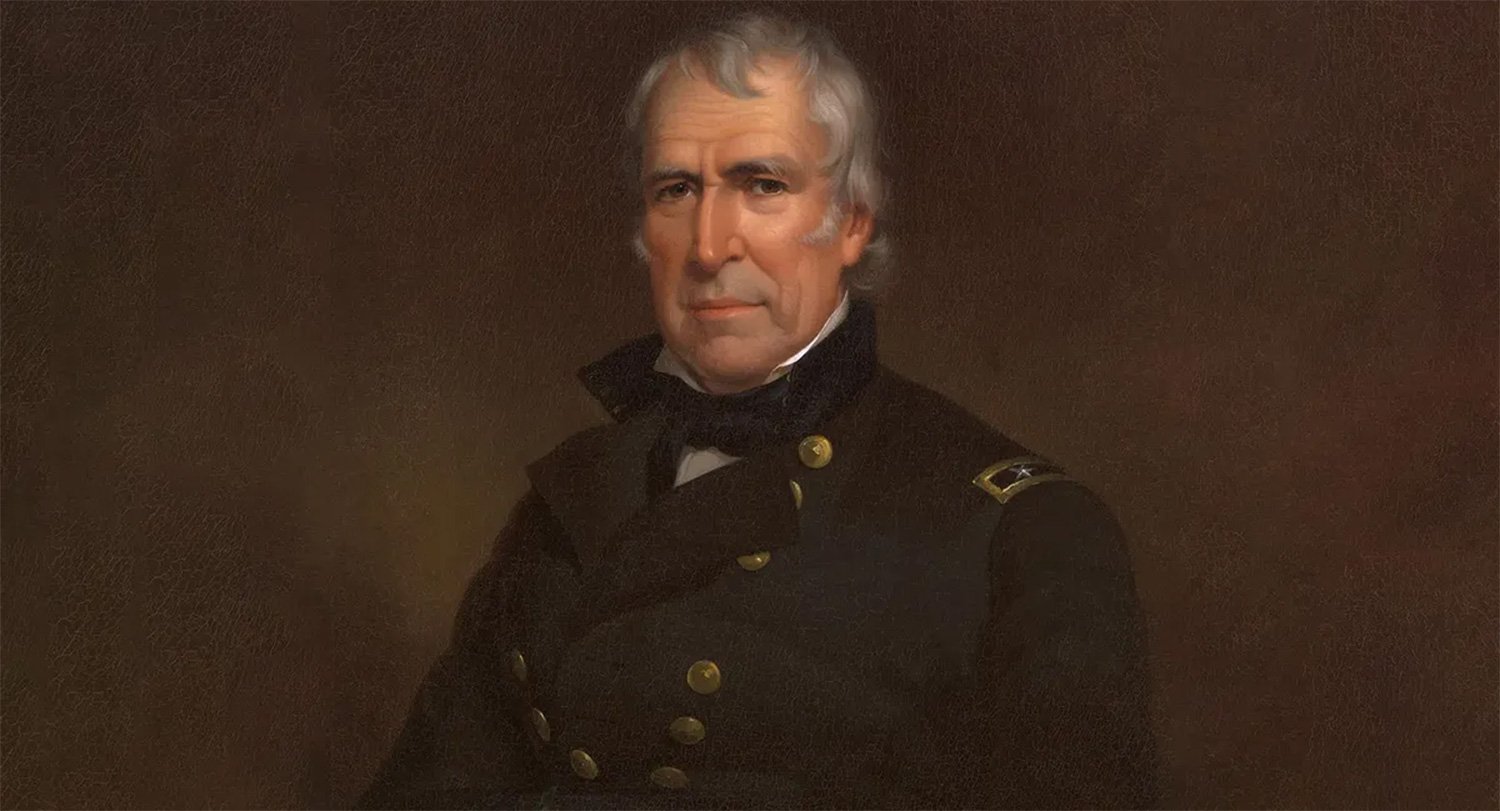

President Zachary Taylor

August 2, 1847